By Ananaya Mittal

Four Types of Female Ghosts You Will Encounter And What They're Distracting You From

Horror is widely said to be having a “feminist moment”. Critics celebrate films like The Substance and the Scream franchise for having reclaimed the “final girl”. At the same time, there is something unsettling about the reasons why horror media is widely centred around women in the first place. Unlike many who argue it as a useful metaphor for the female experience, this essay explores how “horror” as a genre classification is used to make patterned, regular violence against women feel exceptional enough to consume as entertainment. The relevance of this genre classification is that its ramifications extend beyond aesthetics; they are political and economic. It is estimated that horror generated substantially more than $1 billion at the global box office in 2025, while true crime podcasts dominate streaming platforms. The question isn’t necessarily whether we should consume these stories; we inevitably will, but rather what work the category “horror” does to make that consumption feel permissible rather than extractive. I don’t think awareness changes anything in this context, as we’ve been aware for decades, yet the industry keeps expanding. Alternatively, an understanding of what the genre itself accomplishes as a political act, and why that might be the point, seems to be a more productive outlet for discussion.

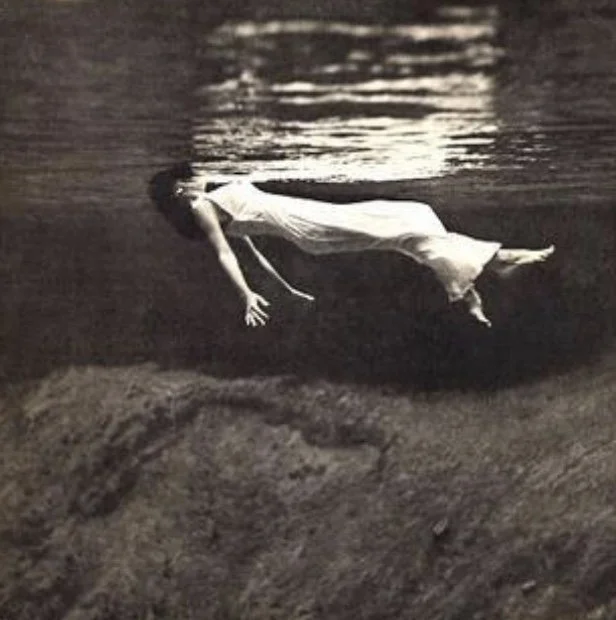

Type One: The Wronged Bride

She’s wearing white. Murdered on her wedding day by a spurned suitor or the groom himself. She haunts the hallowed venue. Every historic hotel has one, The Stanley, Cecil. In Singapore and across Southeast Asia, the Pontianak tells a parallel story: the spirit of a woman who died during childbirth or at the hands of men, returning to exact her revenge. But stripping away the supernatural, the tropes tell the tale of a woman killed by a man she knew, at the moment she entered an institution that statistically endangers her. In 2023, around 51,100 women and girls were killed by partners or family members, one every ten minutes.

It’s not a surprise, then, that this story works well as a ghost fable. Simone de Beauvoir argued in The Second Sex that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”, that femininity is constructed through social rituals and expectations. The bride represents the completion of that construction markedly: a woman who has successfully performed femininity, achieved her social purpose, and conveniently died at the moment of maximum symbolic achievement. She’s frozen in white, forever beautiful, forever a paragon of archetypal female duties.

By making her death supernatural, the ghost story becomes exceptional rather than epidemic. The haunting suggests abnormality, but femicide within intimate partnerships isn’t abnormal at all; it has robust statistical patterns, documented risk factors, and established timelines. Calling it a ghost story conveniently makes systemic violence consumable. And we do consume it. Ghost tourism generates a significant slice of the wider dark-tourism economy. The Myrtles Plantation in Louisiana built its entire ghost brand around “Chloe”, a fictional enslaved woman whose alleged story of sexual coercion and murder has been repackaged as romantic tragedy. Historical records show the Woodruff family owned enslaved people, but no records exist of anyone named Chloe. The story was conceived in the 1950s when the plantation’s new owner heard about a ghost in a green turban and fabricated the narrative to enhance the property’s mystique. The economic model is clear: dead women, particularly young and conventionally beautiful, become profitable when properly aestheticised. When those women are also Black, enslaved and denied sovereignty over their own narratives, the exploitation compounds. The intersection of race and gender violence is rendered amusing, while the historical realities of sexual coercion and brutalisation get erased.

Type Two: The Hysterical Woman

A woman experiences something disturbing. She reports it. No one believes her; she’s imagining things, being dramatic, hysterical. Then, when things go horribly wrong, everyone has the realisation that she was right all along. This is the entire structure of The Yellow Wallpaper, The Haunting of Hill House, and Rosemary’s Baby. Charlotte Perkins Gilman's 1892 story described the “rest cure”, a real treatment that confined women to bed and forbade intellectual activity.

Removing the supernatural framing of these narratives, and you’re left with another unsurprising truth: women’s testimony being systematically dismissed until disaster provides verification. Such forms of medical misogyny are pervasive; women wait longer in emergency rooms and have pain attributed to psychological causes, endometriosis takes 7-10 years to diagnose because women's pain is minimised. In the UK, Black women are four times more likely to die in childbirth, not because of biological differences, but because their reports of complications are dismissed until it’s too late. The horror genre seems to validate women by proving she was right, but as Gilbert and Gubar analysed in their seminal essay on Victorian literature’s treatment of female madness, the “madwoman” (Bertha Rochester in Jane Eyre; Catherine Earnshaw in Wuthering Heights) represents everything the proper heroine must repress to be socially acceptable. The madwoman expresses rage, sexuality, and resistance, and is punished with confinement and death. But crucially, her existence allows the heroine to remain palatable. Jane can be good because Bertha is mad.

Applying this to the “hysterical woman” horror trope, it’s evident that the genre appears to vindicate women’s testimony, but only posthumously or through catastrophe. The woman’s word alone is never sufficient. She needs disaster as corroboration, and once she has it, she’s either dead (and therefore safe, containable, and no longer making demands) or traumatised (and therefore sympathetic in a way that doesn’t require structural change). The genre doesn’t challenge the dismissal of women’s testimony because by creating a narrative structure where dismissal is essential to the plot, it becomes integral to the tale. In this way, horror media paradoxically reinforces the very epistemic injustice it appears to expose: women must be disbelieved for the story to function, which implicitly validates the logic that women’s testimony requires extraordinary proof.

Type Three: The Mysterious Death

In 2013, Elisa Lam was found dead in a water tank at Los Angeles’ Cecil Hotel. Footage of her distress circulated online, and amateur internet sleuths turned her final moments into a puzzle: demons, conspiracies, murder. Netflix later repackaged the case into a hit documentary that topped the streaming platform for weeks.

But the facts were never mysterious. Lam, a young woman travelling alone and experiencing a mental-health crisis, drowned accidentally after going off medication. This is by no means an isolated case either; true crime’s obsession with and treatment of women follows a pattern, and Lam’s story exemplifies its most troubling mechanics. Achille Mbembe’s idea of necropolitics helps explain this: power extends beyond deciding how people live to deciding whose deaths become visible, meaningful, and profitable. Lam had no sovereignty over her own narrative; her death generated clicks because the market has learned that young women’s suffering sells.

Calling her death “mysterious” transforms systemic failure into spectacle. “Woman dies amid inadequate mental-health support and hotel negligence” indicts institutions, whereas “mystery at the haunted Cecil Hotel” has a catchier ring to it. The label of true crime or horror provides the interpretive distance that turns preventable deaths into entertainment, converting policy failure into plot.

Type Four: The Vengeful Ghost

The argument goes: horror provides necessary symbolic space for female rage. Women can’t express anger while alive without social punishment, so the vengeful ghost becomes the only form their rage can take. But returning to Bertha Rochester, the madwoman in the attic, her rage liberated no one. She burned down Thornfield, blinded Rochester, and died. Her destruction made Rochester manageable enough for Jane to return, a kinder, humbler patriarch. Bertha’s rage was narratively useful without challenging patriarchal structure. Modern horror does the same thing. The vengeful ghost can haunt but can’t organise, can’t lobby for change, can’t testify. Her rage is spectacle, not praxis. And the catharsis we experience watching her revenge prevents rage from spilling out of theatres and into courtrooms or legislatures.

Silvia Federici’s analysis in Caliban and the Witch reminds us that capitalism was built on the subjugation of women’s bodies and labour. That witch hunts were not superstition but social engineering methods which contrived public punishments to terrorise women who lived or worked outside the patriarchal order. The vengeful ghost is that witch reborn: her power rendered decorative, her anger depoliticised by genre. Horror keeps her visible but harmless.

The Substance (2024) makes this dynamic literal. Elisabeth Sparkle, a woman aging out of Hollywood’s usefulness, injects herself with a youth serum that devours her. The film’s “substance” is the very process already consuming real women: the beauty industry’s extraction of wealth through manufactured insecurity and self-surveillance. By framing this as body horror, the film softens the accusation. The genre signals exceptionality; that this act is extreme, grotesque, a fictional hyperbole loosely based on reality. But the reality it mirrors is entirely mundane: a global cosmetics economy built on disciplining women into self-hatred. No supernatural explanation is needed, only a willingness to see that the horror was never in the ghost, but in the system that keeps calling her one.

What the Genre Accomplishes

When something happens with statistical regularity, we call it reality. Car accidents aren’t a horror genre; heart disease isn’t a horror genre. But women being killed by partners, their testimonies being dismissed, and pain being minimised, these have datasets, risk factors, and established patterns. Yet we classify them as horror.

That classification isn’t neutral either, as it performs the ideological work of suggesting that we can imagine penny dreadful horror stories more easily than a world where women’s fears are ordinary, explicable, and preventable. Even critique is absorbed by this system. You can consume true crime “critically”, feel ethically self-aware, and still feed the demand. Awareness becomes another product to monetise. This essay isn’t exempt as it too participates in the same circuit, using dead women’s stories to critique the commodification of dead women’s stories. Self-awareness refines the consumption rather than resisting it.

But in my view, recognition still matters, because naming is not descriptive but rather, generative. As Judith Butler reminds us, categories don’t merely reflect reality; they produce it to some extent. So the taxonomic decision to call something “horror” not only misconstrues the issue as an aberration rather than infrastructure, but also determines what responses become thinkable. Refusing that term doesn’t solve the problem, but it does reorient the gaze away from metaphor and toward materiality.

Margaret Atwood elicited perhaps the simplest articulation of this: “Men are afraid women will laugh at them; women are afraid men will kill them”. We have built a billion-dollar industry on the latter. The first act of refusal, then, is linguistic, to stop calling structural violence “horror” and start recognising it as what it is: quotidian, predictable, and human-made. Not a story that needs a better ending, but a condition that itself must end.